A Picture is Worth a 1,000 Words — A Look at Teaching Science With Comics

By Julia Turan

“Comics are like cookies, I may choose one over another but I love them all. It may have sweet potatoes in it but it’s still a cookie,” confessed MK Czerwiec, Registered Nurse and Medical Assistant, who loves to talk about the power of comics.

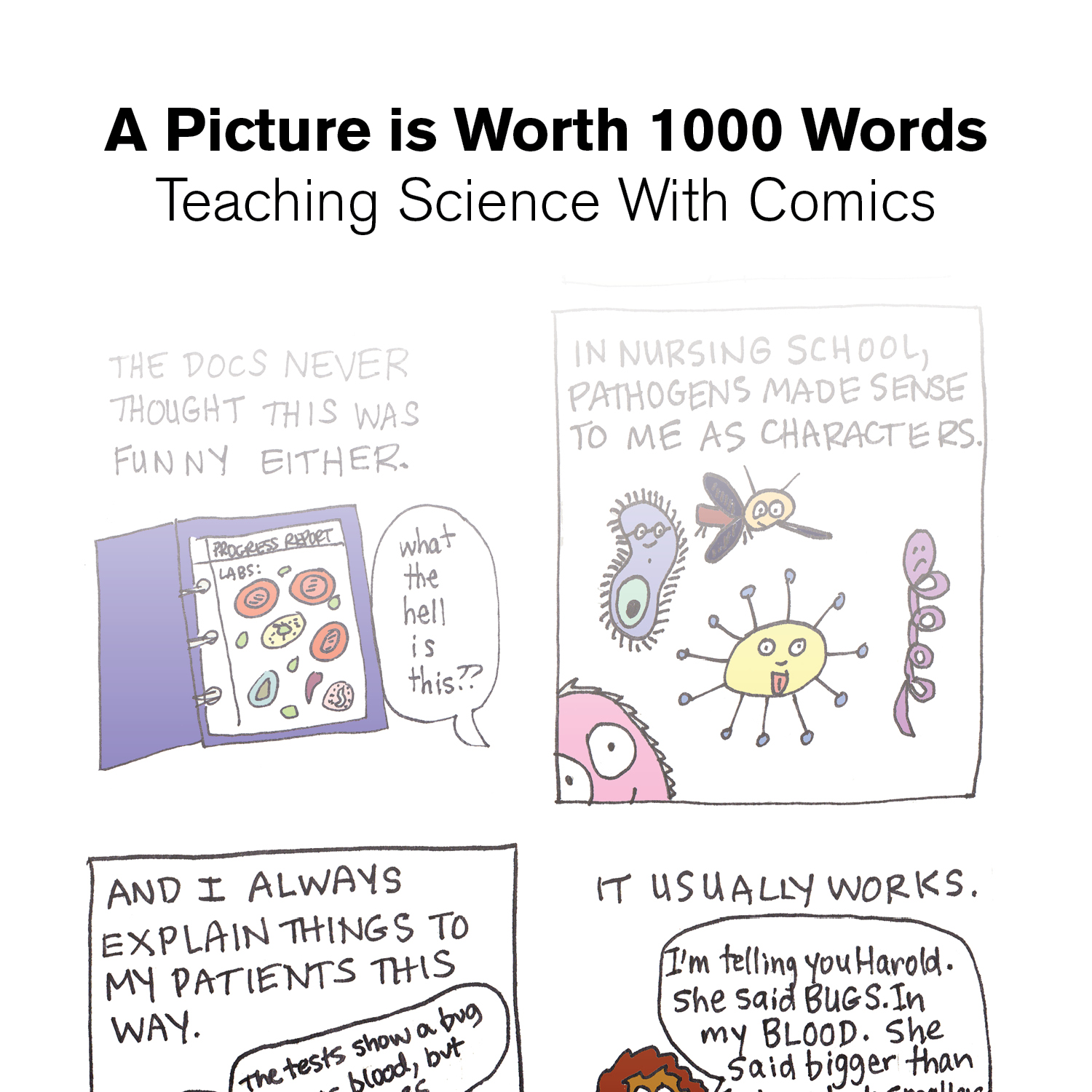

At “A Picture is Worth 1000 Words—Teaching Science With Comics,” MK Czerwiec opened the audience’s eyes to the field of science comics and their power.

Czerwiec first started making comics when she found that using writing to process experiences was failing her, and drawing alone wasn’t cutting it either. Putting the two together, she could better sort through her experiences working at an HIV clinic.

Historically, comics have the reputation of being lowbrow, lesser versions of books. As part of our changing understanding of media, our appreciation of comics is growing and people are increasingly recognizing the power of this medium.

“The grid itself forces you to break things into a stepwise progression, it forces you to impose a story and to look at things in a sequential way,” she explains.

By blending together words and pictures, comics have the ability to convey ideas with greater economy than either alone. Teacher can use comics to help students learn to integrate information in new ways, both when reading or creating comics. Anyone who is grappling with an issue can use comics the way Czerwiec did to process and cope with emotions.

Comics are defined as sequential art that conveys a narrative and often incorporates text. They encompass many genres beyond superheroes.

Czerwiec breaks down science comics into two types: illustrated didactic and narrative comics. Illustrated didactic comics try to teach a lesson using pictures and words in a sequential fashion. Narrative comics on the other hand are stories that are either plot or character driven. Illustrated didactic comics provide explicit conscious learning whereas narrative comics utilize implicit incidental learning. Combining both of these approaches makes for the most interesting and educational science comics.

You might be thinking: this is all well and good, but I don’t draw. Czerwiec posed the question; if four-year-olds won’t draw, we worry, but if a 40-year-old won’t draw we think that’s normal. Why is that?

Czerwiec describes our fear of drawing as such: “I see drawing as this amazing treasure chest and I think of the I Can’t Draw gorilla sitting on top of that chest. But look at him, he is really sweet and cute and I bet if you just sort of threw a banana over there and distracted him, he’d leave and then you could open up this treasure chest.”

Everyone has a visual language. It’s just a matter of overcoming this fear and beginning to create using this language.

What better time to start reading or creating comics than now. As the writer and educator Jonathan Kozol puts it, “Words and pictures lead to a dazzling dance of the dialectic that propels us into asking question we have never asked before. And this is really a great moment for comics.”

–Julia Turan triturated, pipetted, imaged, and analyzed, during her undergrad years studying neurobiology. Since then, she has shifted into the world of science communications, hoping to promote a language of science legible to all. Julia is currently completing an MSc in Science Communication and Public Engagement at the University of Edinburgh. Follow this link to subscribe to her weekly newsletter of five worthwhile science stories: http://tinyletter.com/juliaturan. Or follow her @JuliaTuran.

To watch a video of this program, tune in to our YouTube channel, C2ST TV: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZPpF4CIHkM