Brains of ‘SuperAgers’ hold secrets to long, mentally agile lives

By Colleen Zewe

What is the secret to a long life with undiminished mental agility? Researchers in Northwestern University’s SuperAger project aim to discover the clues by looking at those who have aged with a sharp mind.

SuperAgers are people over age 80 who have memory performance at least as good as those in their 50’s and 60’s. The memory performance of SuperAgers never ceases to surprise the study’s lead author Dr. Emily Rogalski.

“We didn’t necessarily suspect that SuperAgers’ brains would look more like 50-year-olds than 80-year-olds,” said Rogalski, an associate professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “That’s pretty profound, right? To think that you’ve lived 80 years of life, but yet your brain looks like a 50-year-old brain. That’s kind of a dream come true that your brain looks that much younger.”

Rogalski and her fellow researchers at the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease look for genetic, biologic and psychosocial factors that allow the SuperAgers to maintain superior memory performance.

Emily Rogalski has devoted her career to studying SuperAgers and finding connections between their brains and how we can treat Alzheimer’s. (Feinberg School of Medicine)

The life stories and the social ties of SuperAgers reveal significant clues on how to age well, but the physical structure of their aging brains also provides more fundamental discoveries.

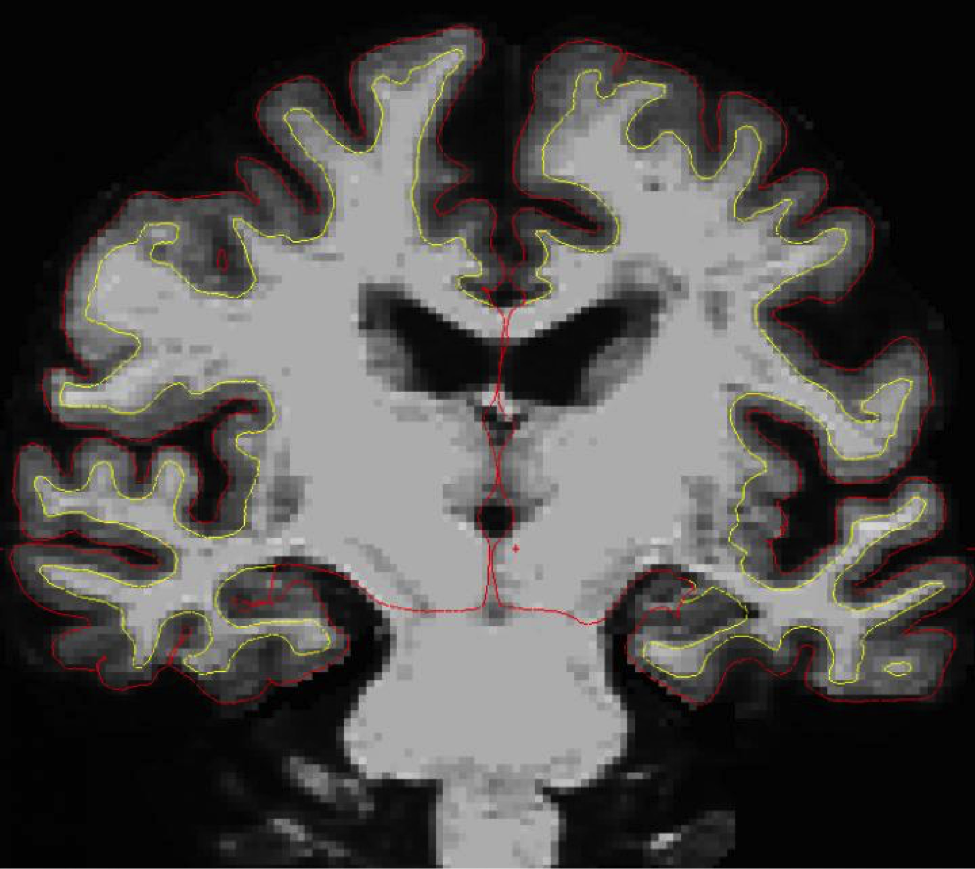

The researchers have found that, compared to other elders, SuperAgers have greater cortex volume and thickness. The cortex is the outer layer of the brain, and Rogalski compares it to the bark on a tree. As we age, the cortex thins, causing the brain to become literally smaller. However, the SuperAger researchers found that SuperAgers’ cortices are thicker, and also shrink more than two times slower than average agers. Their youthful cortex may help SuperAgers resist age-related cognitive decline.

“This this study gives us some evidence that SuperAgers might be on a different trajectory of aging,” she said.

In this MRI scan of a SuperAger’s brain, the portion between the yellow and red lines is the cortex. The SuperAger’s cortices shrunk over two times more slowly than average-age peers’, which may contribute to their superior memory performance. (Northwestern University)

With SuperAgers, her hope is to turn learn how to help people have long, high-quality lives. Though modern medicine helps people live longer lives, Rogalski knows those last years are not always the best. She hopes researching SuperAgers can unlock ways to help people live fuller lives.

One way she hopes to achieve this is by looking at the SuperAger’s personalities. Though people can’t take immediate action on cortical thinning, they can act on their own outlooks to help improve cognitive function later in life.

Rogalski and her team conduct long “life story” interviews with the SuperAgers and ask them to think of their lives as a book. Then, with the Northwestern’s Foley Center for the Study of Lives, the qualitative data is quantified.

The study also examines lifestyle factors of the SuperAgers. They’ve found that SuperAgers endorse strong social ties. In a 42-item questionnaire called the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale, SuperAgers scored a median overall score of 40 in positive relations with others while the average-aging control group scored 36.

“These results are consistent with other research emphasizing the importance of social contact wellbeing,” Rogalski said. “If we think about that there might be some brain benefit to also having an attitude or maintaining friendships, that’s not something you need to change any genes for.”

“It’s important to look at the other side of the coin there and how psychosocial and all of their experiences got them to where they are today, too,” she said. “There’s more to understanding SuperAgers than just the number of microglia or plaques and tangles or genetic influence or the thickness of their brains and these very sciencey, biologically driven factors.”

One potential genetically driven factor is linked to the MAP2K3 gene. The researchers compared the SuperAger’s DNA sequences to cognitively-average individual’s, and found that the SuperAger’s did not have the typical variant of the MAP2K3 gene.

Typically, when MAP2K3 is activated, it signals a cascade of changes resulting in inflammation and potential neuronal damage in microglia cells, a type of cell in the brain and spinal cord.

“A signaling cascade involves a set of proteins that are linked to each other, and influencing one leads to changes in the other proteins downstream of it in the link-chain, to result in a final outcome, in this case inflammation,” said Changiz Geula, a fellow SuperAger researcher.

The MAP2K3 gene is activated by many factors, including environmental stress and chemical alterations triggered by cellular stress. Cells can become stressed for a wide variety of reasons, including exposure to toxins and changes in temperature.

Inflammation in the microglia has been linked to memory loss, and the SuperAgers’ unique MAP2K3 variant may induce lower activation of MAPK, resulting in less inflammation and memory preservation. However, more works need to be done to understand the relationship between MAPK genes, microglia and memory.

Changiz Geula, a research professor at the Mesulam Center, focuses on the pathological study SuperAger’s donated brains. (Feinberg School of Medicine)

“It’s too early to comment on a gold-mine type of finding, and it’s nothing that’s actionable immediately today,” she said. “But it does tell us that there are maybe some unique variants associated with this group.”

Interestingly, SuperAgers come from a wide variety of backgrounds. They have varying levels of education, and they all have varying levels of physical fitness. Some lead their aerobics classes, while others use a walker. Some report having exercised their entire lives, while some say they have never exercised.

“We’ve found this group of people that have one thing in common: they have good memory,” Rogalski said. “But they have come through all walks of life. We have had a remarkable number of things that have been similar across the group given their different backgrounds and life experiences up until now.”

The SuperAger study is funded in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Rogalski is continuing to recruit new SuperAgers, who are asked to donate their brains at the time of death, and Geula is currently studying those brains. Rogalski hopes this research will help discover new clues and information to help older adults live long and live well.

“Sometimes when you have a complex problem like that, what’s helpful is if you turn it on its head,” she said. “The goal is to not only understand Alzheimer’s disease, but also help individuals live long and live well.”